When the reality of the need to be more than a one-trick pony sinks in for an author, the pressure mounts. How can you write fast enough (and well enough at the same time) to make a living at it? Maybe you’re trying to fit writing in around a day job/life. Maybe you’ve given up the day job and are terrified you’ll starve. Most authors (the vast, vast majority) find that their income doesn’t become substantial until they publish four to six complementary books, if ever.

If you’re like me, your first book took you five years to write. If you’ve gotten to your second, it was a little faster, but not much. And even if you’re on to your third, you can’t believe it’s not getting any easier. Plots don’t formulate themselves, and characters don’t break the third dimension without blood, sweat, and a lot of tears.

Writers more successful than you, a la Steven King, advise you to write 1200 un-outlined words a day. But that’s not getting you where you want to go. It’s not resulting in tight, suspenseful, and numerous books with your name on the spine. So how do you get from where you are now—glassy-eyed, numb-brained, and drooling—to “the end,” over and over, with less work, and less time invested in a better product, each time?

-

Brainstorm with a story partner.

I can daydream like nobody’s business. Sometimes I even feel like I emerge from these fugue states with ideas. But as soon as I try to commit them to words, they fizzle. It takes an enormous amount of my time and energy to generate half-baked schemes and even longer to wrestle them into something.

But if instead I sit down with a brainstorming/story partner and talk it out, their ideas spark mine, and vice versa. One of us sees the gaping holes and we redirect the plot line. Another of us throws out a bad idea which generates a good one. We both feel it when a story takes off in the right direction. We goad and prod and cajole each other on and cover far more ground, more effectively, than we do alone. We talk about current events and we talk about history and we talk about pop culture and art and music and sports and love, and anything that will stimulate a good story.

Some writers take this to a whole ‘nother level with brainstorming groups. The more the merrier, if you can keep people focused on forward progress instead of analytical discussions or grandstanding, at least. It all comes down to working with people with whom you mesh and who you trust. Whether that’s one or ten.

Or none.

If this idea doesn’t work for you, don’t do it. It just works fabulously for me. It’s my fast-plotting ace in the hole.

2. Write an “outline.”

Do I really outline my books in I.A.1.a.i. format????? Hell-to-the-no. But do I “outline”? If by outline you mean do I make a list or bullet points and start writing down ideas in roughly sequential order to comprise rough scenes and rough chapters and rough acts leading up—roughly—to a rough ending, then yes, I outline. And it helps tremendously. As long as I don’t make it so formal and regimented that it stifles me. It’s a free flow. Diarrhea of the hands. Ideas before order. Output over exactitude.

Most of the time I write a list of one to forty. That’s how many chapters I expect my 100,000-word book to have. Roughly. I draw lines to separate my list of numbers at the point in forty chapters that I expect my opening to give way to act one, act two, act three, act three extension, and ending. Then I scribble in a beginning, a point of no return, a total protagonist meltdown in the beginning of act three, the climax, and the ending. Next I start filling in the plot/character/subplot progression with rising tension in each scene, and within in each scene, making sure I beat my protagonist down mercilessly at every opportunity and all leading up to each of the big turning points that I marked originally.

Usually, it’s all falling apart for me by this point. I can’t help myself and I either a) go off on a tangent and write too much and realize I’m drafting the story in my outline or b) get on Facebook and waste three hours and wonder why my outline isn’t writing itself. Whichever I do, I also discover about this time that my story sucks and it’s boring and I hate it and I can’t write it and there’s no way to get from point A to B.

But I keep going. Or not. If not, I go back to my brainstorming/story partner and beg for help. Mostly I keep going until I realize that I have no idea how to write a story when I don’t even know the characters in it. And that’s a sign.

3. Bullet-point your characters.

So I do some character study. Nothing excessive. Bullet points. Sentence fragments. Lists. As fast as I can, I close my eyes and let the character speak to me about who she is, and I go ahead and and make a record of it. Because this is where all this stuff belongs. In her character study. Not in my book. And if I know these things about her, I can write her in the story because she’ll be real, and not just some placeholder stick figure that I’m using mercilessly and in a most demeaning way because I can’t be bothered to do the work of figuring her out.

If I write without this “knowing,” my story will fall apart because I can’t plot if I don’t know how people will act and react, or how they know each other, or where they were Saturday night when somebody bludgeoned our vic with a frozen pork tenderloin. I’m good, but I’m not that good.

4. Start a synopsis.

By this time I’m itching to write and my fragments start growing verbs, and my bullet points are fully diagrammable sentences with correct punctuation. Half the time, I’ll give in to the madness and write a first chapter. Sometimes (the other half of the time), I hold firm and decide to test my plot one more time in the form of an in-voice synopsis. This does two things for me. Well, three, if you’re counting. First, it gets me in voice. Duh. Second, it tests my plot and the story arc for my main characters. Third, it gives me something to revise that later I will use to develop my story blurb from. Or, you may find it’s part of the package you use when you pitch your book to agents or publishers.

Synopses are never wasted and never a waste of time. But I confess I do not always do them. I just write better books faster when I do.

5. Begin.

So I’ve been brainstorming my book, dreaming about it, outlining it, character studying it, and synopsizing it. How long does this process take? Days. Weeks. Months. Years. I’ve found that the longer I “live” with a story before I write it, the faster the writing process will be. I write better books if I have stories in different phases of their life cycles going on all at once. I’m processing copyedit on one while I am first-drafting another, while I am having periodic brainstorming sessions on new ideas for a third.

When the time comes that I allow myself to take the bit in my teeth and WRITE, I don’t worry about the first sentence. I’ll revise that later. I just get going and write. It’s like diving off a high dive. Don’t overthink it. Just bend your knees and push off your toes and get ready to fly. Your take off may not be graceful, but you’ll end up where you’re headed anyway.

6. Write until you get to “the end.”

But, when I begin, when I write “once upon a time” or something like it, I write until I get to the end. I mean it. I write without editing the previous day’s work until I get to the end.

It’s hard and it’s horrible. I make a zillion notes about things to go back and change in earlier parts of the book as my subplot falls apart and my killer obviously is Betty Lou instead of Ralph and my protagonist quits her job and dumps her boyfriend, and I hadn’t seen any of that coming. But I don’t turn back and revise. I just keep making notes and writing the book it’s morphing into.

Does that sound like Hell to you? It’s pretty close. It’s also effective. I don’t waste my time editing work I’ve learned I will probably completely change or cut once I figure out what my story is. And I won’t know what my story is until I get the whole thing out.

Go ahead, revise your first chapter for two or three years if that works for you. I’m here to tell you how to plot and write books faster, but you can do it however you want. Imagine adorable winky emoji here.

7. Revise once.

After I get to the end, I give myself a break of a week or two or however long I need. Then, when I revise, I do it with the same rigor as when I wrote the book draft. ONE TIME. This means I pull all those notes together that I made in the first draft and I deal with them as I come to them. I go through a One Pass Revision checklist that is the same and yet different for each book, scene by scene. (For more on this, read this post). I don’t leave a scene until I think it is as good as I can make it at this point, and fully good enough to send off for developmental edit. Then I move on to the next. As I make changes, this necessitates changes down the line (or in earlier scenes). I make notes. When I get to those later scenes, I make those changes. When I get to the end, I can revise the earlier parts.

But here’s something important: often those notes themselves change. If I go back and make a series of cascading changes before I finish my one pass revision, I might make all of them for nothing. So instead I keep moving forward, and only make the changes when I come to them. It cuts down on so much wasted effort.

When I’m done, I hand the book off to advance readers, I consider their suggestions, make changes if I think I should, and then ship the book off to a developmental editor.

8. Repeat.

And then I do it again. For a new book. I’ve started doing my outline for the next book while my book is at developmental edit. Then, after I’ve made any changes I need to and while it’s in copyedit (later), I draft the next book.

See how that works? Because it does. It really does, for me.

***

Truth time: Did I achieve this on my first novel? NO. Not on my first, second, third, or fourth. But I got closer each time, and by my fifth, I did. And I have done it ever since.

Why?

Because I want to be prolific. To make money as a writer. To write mysteries with tights plots, but quickly, and efficiently.

And I want it to get easier. Which it hasn’t. Just faster. That’s good enough for me for now, though.

For tips like these and many more, check out my classes on the SkipJack Publishing Online School (where you can take How to Sell a Ton of Books, FREE).

Your tips for plotting great books, and doing it efficiently and somewhat quickly are gratefully appreciated in the comments below.

Pamela

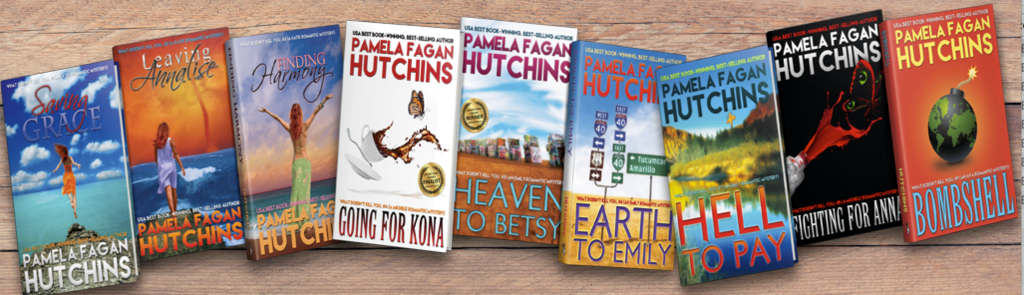

Pamela Fagan Hutchins, winner of the 2017 Silver Falchion award for Best Mystery (Fighting for  Anna), writes overly long e-mails, hilarious nonfiction (What Kind of Loser Indie Publishes, and How Can I Be One, Too?), and series mysteries, like those in her What Doesn’t Kill You world, which includes the bestselling Saving Grace and the 2015 and 2016 WINNERS of the USA Best Book Award for Cross Genre Fiction, Heaven to Betsy and Hell to Pay. You can snag her newest release, Bombshell, if you’ve already run the rest of the table. She teaches writing, publishing, and promotion at the SkipJack Publishing Online School (where you can take How to Sell a Ton of Books, FREE) and writes about it here on the SkipJack Publishing blog.

Anna), writes overly long e-mails, hilarious nonfiction (What Kind of Loser Indie Publishes, and How Can I Be One, Too?), and series mysteries, like those in her What Doesn’t Kill You world, which includes the bestselling Saving Grace and the 2015 and 2016 WINNERS of the USA Best Book Award for Cross Genre Fiction, Heaven to Betsy and Hell to Pay. You can snag her newest release, Bombshell, if you’ve already run the rest of the table. She teaches writing, publishing, and promotion at the SkipJack Publishing Online School (where you can take How to Sell a Ton of Books, FREE) and writes about it here on the SkipJack Publishing blog.

Pamela resides deep in the heart of Nowheresville, Texas and in the frozen north of Snowheresville, Wyoming. She has a passion for great writing and smart authorpreneurship as well as long hikes and trail rides with her hunky husband, giant horses, and pack of rescue dogs, donkeys, and goats. She also leaps medium-tall buildings in a single bound (if she gets a good running start).

I’ll take an idea or something that has happened in my life, build on it and make a fictional story around it. I have to write to get to know my characters because they are like getting to know a new friend. They’ll show themselves a little bit at a time and they also have a mind of their own and don’t always do what they are supposed to do! So that means a lot of revising and editing along the way. I also have to re-read what I wrote the day before to get in the groove, or get into character. Sometimes it takes me five minutes, sometimes 30 minutes or more. Once I’m “there” the writing goes faster, not easier, just faster. I try to write everyday, even if it’s only two paragraphs because they way I look at it, that’s two paragraphs toward finishing the book. This works for me, maybe not everybody else.

So true–two paragraphs more toward finishing the book.

I am a big fan of life reimagined. I find that most of my writing is truly what I know, not what I make up. When I was young, I used to walk around daydreaming, talking to myself sort of. To me, that was the best. I was making up stories and living within them. Telling them to myself, starring in my own show. Now that I record my books, I’m sort of doing the same thing 😉

YOWZA! Just reading your process makes me tired! To get a better understanding, will you please share WHO your writing partner is….another author, your husband?

Thanks for writing this post for little ol’ me. It was very helpful and insightful.

My husband. It just turns out he is incredibly good at plot, and he loves to talk about my books, so we talk on road trips and walks and over meals. We discuss tension, progression, pacing, red herrings, “clues,” and characterization. My friends brainstorm with other writers.

Gotcha. Thanks for clarifying, and for outlining your profound process. m3

I love that I get to participate with you in the process. We have had some great hiking or walking conversations about plot. Its like watching it unfold infront of you while we talk. I appreciate your inclusion of me into that piece.

Just another of the ways we are good together <3